I’m currently re-reading the Sherlock Holmes series, and one of the interesting aspects is the glimpse into the standard of living in the late 1800s. In some cases I’ve found myself asking, why don’t we have that option today!? In others, it’s clear that purchasing power does not at all correlate directly to inflation. Let’s take a look at a few examples from the books.

Dr. Watson’s Income: A Study in Scarlet (the first Holmes story)

Published in 1887 but set in 1881, A Study in Scarlet is one of the four Holmes novels and introduces the reader to Sherlock Holmes through his introduction to Dr. Watson. They only meet because they are each seeking a flatmate to share costs and, in Watson’s words, “get comfortable rooms at a reasonable price”.

Medically discharged from his army service as a doctor, Watson has a pension of “eleven shillings and sixpence a day”. There’s an article here that explains old British coins, with images for each of them. A shilling was worth twelve pence, and a pound was 20 shillings, so Watson’s income was somewhere around £330 a year.

Holmes’ and Watson’s quarters at 221B Baker Street (in the West End, a very popular part of Central London then and now) consisted of:

- Two bedrooms, furnished

- A large airy living room with two broad windows, also furnished

- Light housekeeping service included (landlady Mrs. Hudson)

- Breakfast, lunch and dinner service included (also by Mrs. Hudson)

Including meal service was a standard practice at the time, and I’m surprised it hasn’t made a comeback today in busy cities. Nevertheless this is clearly a nice apartment, but not opulent or luxurious.

Income Comparisons

It’s difficult to adjust Victorian-era incomes to modern day currency due to the decimal change in 1971 (upending the entire British monetary system) and the dramatic variations in buying power then to now. Therefore, let’s look at some examples of incomes from that time period, plus consumer goods pricing, and draw some comparisons.

Despite the complaints about his finances, Watson was considerably better off than the working class at this time. References show that a matchgirl (factory worker) would make £30 a year at best, while bank clerks and shopkeepers might average a pound a week. The average annual wage in the middle 1880s in England was under £50 a year.

We have further support that £50 a year was a livable London wage in the Holmes story “A Case of Identity”, when he remarks to a client that a single lady “can get on very nicely upon an income of about £60”.

In the story “The Red-Headed League”, a pawn shop owner is lured away from his shop (for the villain’s nefarious purposes) by a tempting offer of £4 a week, four times what he’d normally make.

In “The Man with the Twisted Lip”, a man described as having an excellent education and a reporter for an evening London paper was earning £2 a week, better than most and likely in a more senior position.

In “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches”, a governess was earning £4 a month (£48 a year) in a standard posting, though we must also provide allowance for the room and board servants received. This story in particular has additional income references: “very few” governesses would make £100 or more a year, and employers could have their pick of women at just £40.

Goods and Services Costs

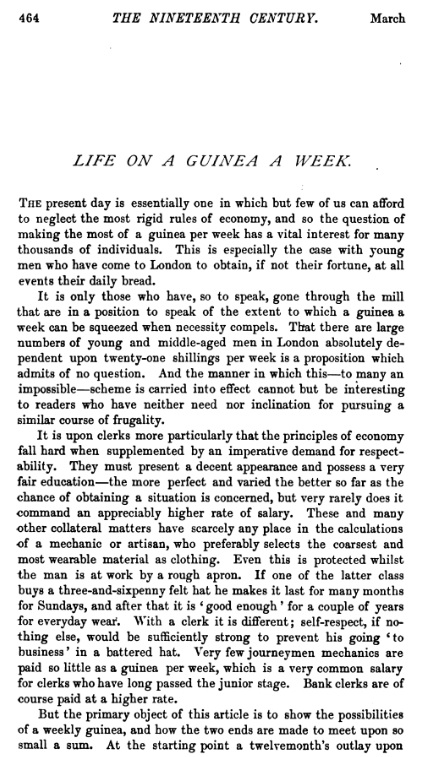

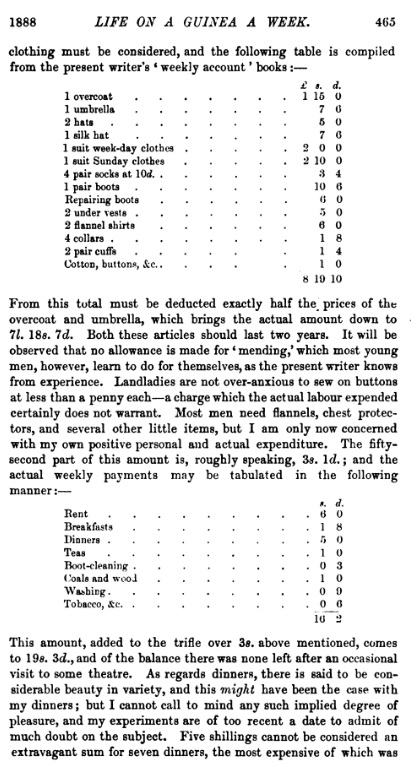

An article published in the British magazine The Nineteenth Century, titled “Life on a Guinea a Week”, provides insights into the costs of goods and services in the year 1888. I found the full article in the archives, that can be viewed for free here.

The first page points out in particular some class issues and how one wanted to be perceived. A clerk is held to a higher standard in public, to “present a decent appearance” versus the tradespeople like mechanics, and therefore had a much higher expenditure on good suits, silk hats, overcoats, collars, and so on. It’s possible to live in London for less, but not if you want to project a “respectable” appearance.

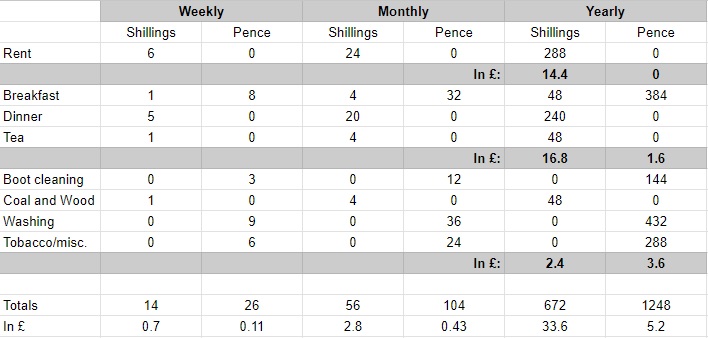

The second page gives an interesting breakdown of these “finer” clerk’s clothing items, with prices, as well as weekly living expenses. £ is for pound, s for shillings (twenty per pound), and d for pence (twelve per shilling). With these examples, we see a yearly cost of around £8 for clothing, £14 for rent, £18 for meals, and £6 for heat, washing, and incidentals.

In total, this is about £47 a year. As the young gentleman says, “there was none left over after an occasional visit to some theatre”.

Additional references for 1880s wages, goods and services can be seen here.

Purchasing Power

Now let’s take a look at inflation versus purchasing power. An annual income of £50 in 1888, adjusted for inflation, is just £8,315 in 2023. That may sound incredibly low, but it’s an increase of over 16,000%.

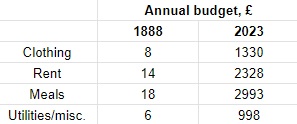

Let’s look at the goods and services costs we just tallied, adjusted for inflation to 2023.

Clothing, £1,330 a year. That seems reasonable for many people, but not with suits and silk hats.

Meals, close to £3,000 a year, for a single person. Harder in London, but perfectly reasonable without too many restaurant meals.

Rent, £2,328 a year. In other words, £194 a month.

What!!!

Wait, you say, that doesn’t include heat and electricity. Even at £4,000 a year, or £330 a month, you won’t be able to stay anywhere in London, even a room rental is near £1000. How on earth was it so relatively cheap for rent in those days? Well, for one thing, remember that there weren’t kitchens or private bathrooms in those rentals. Running water, electricity, furnaces, and so on all dramatically increase housing costs. However, it appears that raw purchasing power was also greater in those days compared to now. Even in my parent’s day, a nickel candy bar is going to cost more than the $0.52 inflation says that it should.

Conclusion

I hope this was an interesting peek into Victorian-era pricing and costs. Whenever I read Sherlock Holmes, I’m always struck by the radical leaps in costs between the classes, and how far a pound could be stretched back then.